Many people often ask me why I try and write novels for children, particularly novels aimed at the 9 - 12 year-old age group. For one thing, I don't have children myself and rarely come into contact with them. Also, being an English Literature graduate and having worked as an editor of an arts and listings magazine, people often assume I should be dedicating more of my spare time to writing more serious, adult novels: arty, brow-crimpling novels with bleak, sombre-looking covers to satisfy the slightly conservative tastes of dusty academics; gritty, hard-hitting stories about death, sex, recreational drug use, life-threatening illness and the brittleness and ephemera of modern day relationships. After all, I've endured a lot of hardship and emotional turmoil in my own life, and my own personal experiences, if you don't know them already, would probably make even the hardiest of grown-ups reach for a tissue and weep (see my previous blog 'My War On AIDS').

But maybe this is one of the reasons why. Maybe there is a desire in me to find some sort of respite from the harsh realities that life has hurled at me over the years, to hark back to a time when imaginary faces appearing in the patterned wallpaper of my bedroom were the most frightening things I had ever confronted. Not AIDS or terrorism or death or war. It was a time when the head-swirling thrill of a fairground ride at Blackpool Pleasure Beach was more satisfying than the yet-to-be-discovered pleasures and pitfalls of sexual intimacy. It was a time of innocence, wonder and discovery, a time before our minds are polluted by the hormonal onslaught of moody adolescence and the acne-ridden sexual awkwardness that follows.

This is not say that everything is wondrous and fluffy and pink in the eyes of a prepubescent child. Emotions are primitive and raw, but the mind of a child can be astonishingly astute. By the ages of nine or ten, most children, if they've been blessed with a decent education, can read quite fluently; and they can be surprisingly sagacious too. They can surf the internet, browse magazines and they are absorbing news and information on a daily basis. They may not fully understand the political and social complexities of the world they live in, but they can certainly grasp the meanings and outcomes of war and death and poverty and injustice. They are already forming opinions about the world around them. And every child has probably witnessed or even experienced first-hand the ugliness of bigotry and prejudice through bullying tactics and cajoling in the school yard. Children can be naive and inexperienced, but they are not fools. And they certainly shouldn't be patronised or talked down to.

Ultimately, I think I write for children because it's fun. Pure unadulterated fun with a capital 'F'. But that isn't to say that writing for children is easy. Far from it. Some established children's writers even argue that writing for children is even more difficult than writing for adults. It's certainly a challenge. In an age when entertainment comes at the push of a button, children bore easily. Their attention spans are limited. Present a child with a weighty-looking book full of pages of descriptive prose and very little dialogue, and the average child would probably recoil in horror. And if a novel or story hasn't fully ensnared their imaginations within the first few pages, the book will be tossed aside like a useless, broken toy, abandoned under a heap of unused action men and armless dolls.

And then there's the question of what literary theorists call 'the implied reader'. Sadly, and entirely due to circumstances beyond my control, I don't have children of my own. But when I sat down to write the first draft of my novel, I already knew that the implied reader imported into my head was myself as a young boy - the shy, dark-haired, freckle-faced boy who would blush easily if spoken to by a grown-up and whose shyness made him quite solitary and lonely. As a child, I was quiet and bookish and, according to my mother, rarely ever seen without my nose in a paperback. Between the ages of eight and twelve, I read voraciously every day: afternoon excursions into Narnia being much more appealing than the knee-scabbing scuffles with the backstreet bullies of working class Lancaster. I read anything I could lay my hands on, vanishing for hours on end into wonderful worlds of words and pictures, rummaging inside the heads of Alan Garner, Roald Dahl, Norton Juster, Kenneth Grahame and Philippa Pearce. It was a thrilling time; and many of the novels I read in the early seventies have haunted my imagination ever since. ('Marianne Dreams' by Catherine Storr still gives me goosepimples after all these years, and images from Ted Hughes' 'The Iron Man' have been permanently imprinted on my brain).

When I began my children's novel I knew that I was writing something I would have enjoyed myself as a child, something that would have filled me with awe and wonder and provided me with a few hours of escapism from the rain-lashed streets of the town I lived in. As I wrote, I found myself connecting with child I once was and using that version of myself to guide me through my story. As I scribbled notes and strummed the keyboard of my computer, memories came gushing back, memories of what I liked to read, of how I spoke and thought, of things that frightened me in the darkness of my bedroom, like the scary faces appearing in the wallpaper. I also began to recall some of the stories I used to write as a child and which were often read out by the headmaster during assembly at school.

In essence, the story I have written, 'Billy Winker and the Library of Dreams', is a dark fairytale set in modern day suburbia (laptops, mobile telephones and computer games are mentioned, but only in passing). It is a story about a ten year-old boy searching for his missing cat. Sounds simple enough, but as the eponymous Billy delivers leaflets and talks to his neighbours, he begins to learn that there is something sinister about the old, crooked house at the end of his street. Intrigued, Billy prompts his neighbours to tell him about the history of the old house and its previous occupants. Fascinated, he listens in awe to his neighbours' tales of adventure, revenge, mystery and horror. All of the stories are vastly different, but all of them focus on the old, creaky house at the end of the street and the various characters who have lived there. Soon, Billy and his new friend, Abigail, begin to unravel the mystery of the house and its current occupant. And as the whereabouts of Billy's missing cat are eventually discovered, Billy and Abigail find themselves in darker, more dangerous waters than either could possibly have foreseen.

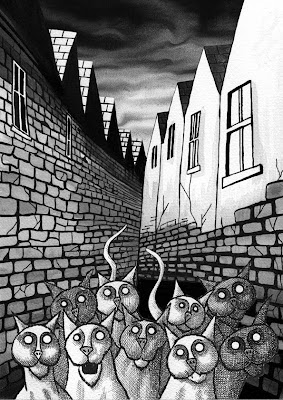

I have written the novel in a quirky, individual style which will hopefully whirl the reader along until the surprise ending. There should be enough touches of the macabre to scintillate a few older readers too, including adults. As I have worked as a freelance illustrator, I have also provided some original black and white illustrations which hopefully complement the sinister atmosphere of the story. A very small selection of these illustrations can be seen on my website.

My hopes of 'Billy Winker and the Library of Dreams' being accepted by a publisher are not ridiculously high. I'm being realistic. I have confidence in my novel, but I am fully aware that the market for children's fiction is fiercely competitive, and that children's publishers and literary agents receive hundreds of manuscripts a week. But at least I'm trying my best. And I am approaching potential publishers and agents in a highly professional manner.

At the moment, sample chapters and sample illustrations are now sitting on a slush pile in an office somewhere, waiting to be perused by a reader. I'm already bracing myself for a few rejections, but keeping my fingers crossed at the same time. In the meantime, I have already started plotting my next children's novel, a story about gruesome dinner ladies. Notes are being scribbled, characters are being sketched and ideas are being jotted down.

And who knows, maybe one day I'll write a story about the nightmares faces that appeared in the wallpaper of my childhood bedroom all those years ago. It'll give you the creeps for sure.